How to Help (Without Enabling) Your Kid: The Four Roles of the Parent

We get this question all the time from parents: “I want to help my kid, because I see that they're struggling, but how do I help without enabling him?”

We tend to go from one extreme to the other:

- Some parents try to “force” their kids to do what they think is “their best,” and then get increasingly frustrated because their child is inconsistent or doesn’t seem to want to do the work.

- On the other extreme, some parents do too much for their kids. I know of a parent of a child with dyslexia who did her son’s homework for him when he couldn’t keep up.

What’s the best way to handle helping without enabling?

First, understand that you have two goals.

- You want to help your kids learn do those things that are difficult for them.

- You want to continue to foster their growth and independence at a pace that makes sense for them.

The key to accomplishing both of these goals is to get clear about how to set reasonable and realistic expectations for your child.

How to Best Set Expectations?

- Shed the “shoulds” – Everywhere we look there are books and resources, teachers, and well-meaning family members telling us what our kids should be able to do. If we make our decisions based on what we think they should be able to do, rather than what they can do, it can be stressful – for your kid, and for you. I work with parents of “complex” kids, and those kids are often 3 to 5 years behind their peers in some areas of development. It’s an important part of the considerations needed when setting expectations. So listen to the advice with an open mind, and then make your decisions in the context of your child’s development. My best decisions always balance my knowledge, my emotions, and my intuition about the situation.

- Meet them where they are – The goal here is to figure out what your kids can do comfortably and consistently, and then raise the bar from there. The reality is that children don’t come in “one size fits all” – and it takes a bit of detective work to figure out what the right level is. Imagine your child climbing the stairs toward independence. Instead of standing on the stair where you think he should be and trying to “drag him up,” walk down to the step where you think he is, and help him map out a plan to get to the next step. For example, if your child doesn’t remember to brush his teeth on his own, but can comfortably do it when you remind him, that is the step he is on. If you choose to take aim on this issue, the next step might be to help him develop his own structure or reminder system that could replace you in the process.

- Let go of the fear – Most of the time, your frustration is based on catastrophizing about some underlying fear you have as a parent. If he can’t remember to brush his teeth, how will he ever get up and go to work every day? If he can’t finish his homework without a battle, how will he be able to get into the college of his choice? Our kids all have their own trajectory. Trust that developing independence happens step by step. Stay on your child’s step, instead of worrying about what might happen 10 years from now!

What is your role?

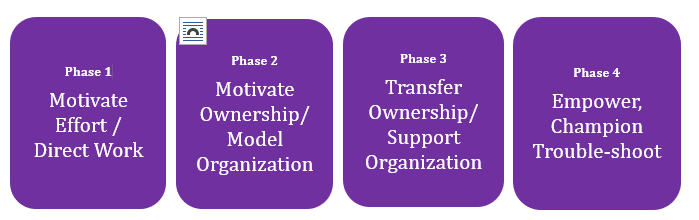

So how do you know when to help and when not to help? There's never a crystal-clear answer because it depends on your child’s development and maturity. In Sanity School®, we teach that parents' roles tend to fall into these four phases:

- Phase 1: Direct

(Motivate Effort/Direct Work) - Phase 2: Collaborate

(Motivate Ownership/Model Organization) - Phase 3: Support

(Transfer Ownership/Support Organization & Execution) - Phase 4: Champion

(Empower, Champion, Troubleshoot)

Article continues below...

Minimize Meltdowns!

Download a free tipsheet "Top 10 Ways to Stop Meltdowns in Their Tracks" to stop yelling and tantrums from everyone!

Phase 1

A parent’s role is directing their work and motivating the effort. You may be telling them what they should be doing and helping them stay motivated to get it done. Kids are expected to fulfill their parents' agenda. (For neurotypical kids, this is often the role of the parent with preschool and elementary age kids.)

Phase 2

This is a major stage of transition. The goal here is to help support your child while maintaining a balance of not enabling. The distinction I like to make is that if you are doing something “for” them it could possibly be enabling; so you might want to think in terms of doing something with them and/or in support of their role, which is more likely to be supporting. (For neurotypical kids, this is often the role of the parent with upper elementary and middle school kids.)

Phase 3

The role of the parent at this level is to continue to foster independence. Consistently ask yourself, "How can I help my child 'own' more of this situation?" Keep in mind that it’s a gradual process. Your child might not just wake up the first day of 9th grade ready to do it all on her own, even if she thinks she can! It will take some encouragement from you to help her take ownership effectively. (For neurotypical kids, this is often the role of the parent with upper middle school and high school kids.)

Phase 4

Eventually, your kids will be living on their own, and ideally that means they'll be managing things on their own, too. That may not mean complete freedom for parents, but it's definitely switching to a more passive role! The parent’s job here, as much as possible, is to support and encourage your (young adult or adult) kids as they “own” their decisions and responsibilities. You want to make sure they know you have their back – at least emotionally – if struggles arise. The point is it’s their life, and as parents we stay conscious of managing how much, or how little, to get involved. (For neuro-typical kids, this is often the role of the parent with older high school and college-age kids.)

Four Phases

The four phases of the role of the parent are not exact, but they can guide you to help your child without enabling. Know that it’s a gradual process, and focus on what you really want for your child, to help them and to assist them in independence. And don’t forget the other goal we tend to forget: enjoy your kids – they are only with you for a short time!

P.S. If you are or would like to be moving into phase 3 or 4 with one of your kids, you might want to read this great article that Elaine wrote when her ADHD teenager moved away from home…