Using Stress to Help Performance, Anxiety and Self-Esteem

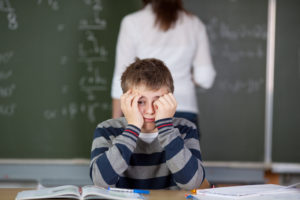

Behaviors of children with ADHD and related challenges of Executive Function are often misinterpreted and viewed as oppositional, defiant, rude or disrespectful. In fact, in many instances, these children are actually trying to take care of themselves and manage their stress and anxiety.

Consider these scenarios:

Tyler is working diligently in his 4th grade math class. Calmly, the teacher announces a two-minute warning to transition to Language Arts, adding, “I really think you're going to like what we'll be doing next.” Tyler keeps working. At the teacher's 1-minute warning, Tyler is still head down and pencil moving. Time runs out. Frustrated, his teacher says “Tyler, I've given you enough time to stop and get ready for ELA. You need to put your paper away…NOW.” It's as if Tyler can't hear the teacher. The teacher says, “You are being very disrespectful. Do you want to lose your free time?” At no response, she takes his paper away, but Tyler grabs it back from her and runs out of the room. Within minutes, Tyler is “apprehended” and headed for punishment.

It's about 4:00 pm. You tell your 10 year-old son, who has been playing very nicely, that he has to do his homework. He claims he doesn't have any, but you've checked the school website and you know he has to write a 1 page essay. You show him the computer screen and he flies into a tearful fit, yelling at you and telling you how “school is SO stupid! Why do they make us do stuff like that? I HATE school. I hate you!”

What's the most likely explanation for these behaviors?

A. These are nasty kids

B. They all have oppositional-defiant disorder

C. They are all the behaviors of unmotivated students

D. These kids have a terrible relationship with their teacher or parent

E. Uh, none of the above?

While these could be the behaviors of an oppositional or defiant student, or one who doesn't get along well with his teacher or his parent, the correct answer, in more cases than you can imagine is E, none of the above. In these scenarios, and in so many situations that occur in homes and schools every day, the behaviors are all created by the same demon. The correct answer is: STRESS.

The Explanation:

When kids are asked to do things that they believe they can't do well or can't do at all, they do what any animal (human and non-human) does: they run, they fight or they hide. This “fight or flight” response is our built-in response to things we think might harm us (which includes embarrassing us), and over which we have little control. Behaviors like these are often misinterpreted and viewed as oppositional, defiant, rude or disrespectful.

In fact, it's likely that they are the protective behaviors of a young human who feels that he or she might not be able to do what they've been asked to do, or do it well enough to gain the respect of others or the praise of teachers or parents.

Very few parents or teachers see this connection. In the scenarios above, the children were doing something that they either liked or did well when confronted with a situation that would require skills and knowledge they did not have, or did not believe they had. By asking them to switch gears, they were asked to move from feeling secure or competent to a zone in which they expect to (yet again) experience frustration, failure and shame.

Kids at all grade levels all across this country are penalized, prodded, promised things, made fun of, embarrassed and cornered by well meaning teachers and parents who are “just trying to get him to do things that I know he can do.” What these kind-hearted adults fail to appreciate is that it doesn't matter what you think a child can do; it matters only what the child thinks he or she can do.

A brain that says, “I can't” is a brain that's under stress. Stressful situations from which there is no escape activates the survival parts of a kid's brain. It turns off the part that's responsible for executive functioning—the ability to make sense of problems or challenges, and come up with strategies to solve or conquer them. In other words, to be effective learners, kids need to use the parts of the brain that get de-activated in stressful situations!

Article continues below...

Minimize Meltdowns!

Download a free tipsheet "Top 10 Ways to Stop Meltdowns in Their Tracks" to stop yelling and tantrums from everyone!

How does this translate to your kid in school?

Kids need to be kept on the edge of their competence. This means that they need to believe that they can do what they've been asked to do without feeling like it's “baby work.” A lot of kids who have been burned by previous failures see each new activity as a threat—something to be avoided.

Remember that kids experience “bad stress” (the kind that turns off the thinking, planning brain) when they don't feel that they have control over what they've been asked to do. To change this mindset, and give them a sense of control, I use something I call “competence anchors.” Here's how it works:

- When stopping an activity that a child knows he or she has done successfully, point out how the next activity is very much like it. Help the child move from known competence to probable competence, reducing the threat and making it more likely that the child will try the next activity.

- To increase the child's sense of control, ask the student to rate the anticipated difficulty level of the new task on a 1 to 5 scale: one thumb up is easy, and five fingers up (the universal stop sign) is hard. This gives you information about how the child perceives the task and her ability to do it.

- If her ratings reveal that she thinks its too hard or that she can't do it, decrease the challenge (give her a lighter weight) until she thinks she can do it.

- After she's done, ask her to tell you whether she had rated the difficulty level correctly, and whether she was right about her ability to complete the task.

This strategy builds competence and confidence, and keeps stress in the proper balance. Successful kids take on challenges that they think they can master, and they believe they can do it. They generate just the right amount of stress to get them ready for a challenging task. The stress they feel is “I can do this” stress, and not mind-freezing “get out of here” stress.

The approach I've described takes stress that could instill fear, and turns it into fuel—the fuel that powers a child's success engine. This is the true “Breakfast of Champions.” I love it when kids exposed to this approach look at a challenging task and say: “Bring it on! I eat stress for breakfast!”

Sanity Is Not Optional

Freaking out? Want to recover your SANITY? We can help you gain the clarity you need. Talk to us and find out HOW!